AROUND PHOTOGRAPHY

EDITRICE QUINLAN

RISORSE

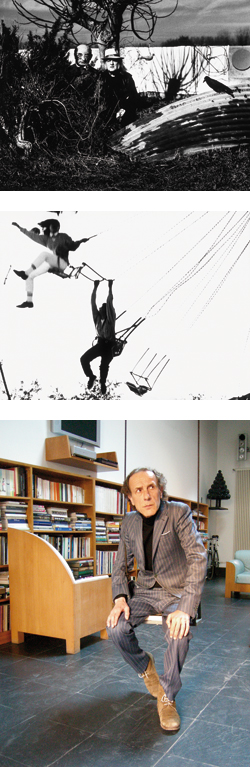

ENZO CUCCHI - COSE MAI VISTE a cura di Roberto Maggiori

Since 2006 an exhibition of unpublished works by Mario Giacomelli has been travelling in Italy and abroad. The exhibition, accompanied by a catalogue published by Photology under the title Mario Giacomelli cose mai viste, features an exceptional curator: the painter Enzo Cucchi. We met him to discuss this experience and his peculiar point of view on photography and art in general….

RM: How did the idea for the exhibition develop?

RM: How did the idea for the exhibition develop?

EC: Very simply, it was high time Giacomelli was gloriously raised on a pedestal and, naturally, only artists can deal with this sort of things. I did not really want to curate the exhibition but it is the artists who authorize an image and decide how to use it, how to put it to rest, how and where to lay it down. Only artists can legitimize the base on which an image is propped up. As for sculpture, or everything else, the base, the pedestal is often more important than the image itself, it is essential. In this case, Mario deserved to go up on a stool.

RM: So, is this the reason why for the exhibition you chose a “modular” arrangement and installed the works higher than usual?

EC: Yes.

RM: What did you like to curate most, the exhibition or its homonymous catalogue?

EC: I liked most Mario Giacomelli’s photographs. If this happened, it is also because Mario was a fellow traveller of mine.

RM: Your fellowship with Giacomelli begun when the photographer from Senigallia was still alive. For example, I remember your joint exhibition Nati in un fosso (Born in a Ditch). How did you meet each other?

EC: As he used to say, we met because we were both born in a ditch.

RM: You both come from the provinces of Ancona, in the middle of Italy. Can we say that your shared artistic sensibility is grounded on this geographical proximity?

EC: I am not at all interested in geographic or folkloristic stuff. Sensibility, imagination, fantasy are just definitions: these things do not exist. That which exists is discipline and signs “pushing” other signs. Obviously one does not get interested in meaningless signs. “Pushing” signs are what you search for and eventually find, and you can find them anywhere in the world.

RM: Are there other photographers for whom you would repeat a similar experience?

EC: Well, it depends on many things. But if you ask me if there are other photographers whom I appreciate and admire, one name for all is certainly Robert Frank. Doubtlessly, he is the best, he is the Picasso of photography. He also photographed a work of mine, the church La Madonna del Tamaro, designed by Mario Botto, for which I was commissioned two important artistic interventions: the aisle ceiling and the apse. When Frank came to photograph the church Botta showed him around. Much to my regret, I could not go along because some pictures where to be taken from the helicopter and I am terrified of flying, the very idea of lifting my feet up off the ground makes me die…

RM: Giacomelli used to photograph from an airplane too…

EC: You see! Perhaps people meet because one has what the other lacks.

RM: How would you define Giacomelli’s work? Provided that a definition, a thought, or an image can define the work of an artist.

EC: I don’t think that Mario’s work should be defined. It can’t be defined. That is an unbearable grown-up habit of the so-called historians and critics who deal with these things.

RM: I am not referring to mere classification categories that can be useful to speed up mutual understanding. I would like to go into…

EC: That is not the point, there is a deep rupture. In short, if you ask me to define something I can only answer that it is impossible. Definitions derive from preconceived and obsolete concepts forged by the intellectuals in general.

RM: Can we move this conversation past preconceived ideas?

EC: I can never take off from the territory of intellectuals. In order to reach a certain point it is essential to keep momentum, whereas in the territory of intellectuals I slide, I slide back.

RM: Do you curate your own exhibitions or do you prefer others do it?

EC: Curators’ exhibitions bore me. I like to install my small dirty things on my own. For me, it is a great occasion to verify how the works function. I have also participated in exhibitions curated by others. They can be gratifying experiences but, still, they have anything to do with neither me nor my work.

RM: Your drawings appear in the catalogue. Were they made specifically for this publication?

EC: I definitely thinks so. Everyday I draw what is around me. It is a question of discipline. Yet I never draw for the sake of drawing or for the sake of illustrating a story or a landscape. Therefore, even if those drawings were not meant to illustrate Mario’s work they relate to it somehow.

RM: I enjoyed both the exhibition and the publication. I find the selection of photographs to be quite visionary and yet still ascribable to Giacomelli. There is a distinct curatorial presence. Yet on the pages of the Corriere della sera, one critic has charged this operation with being too speculative. She claimed that it features discarded photographs that Giacomelli would have never authorized…

EC: The photographs were taken, printed, and archived by Mario, and that is enough. I don’t read newspapers but I look at Giacomelli’s photographs and they interest me more than what is behind them. Who is this person by the way? If you tell me her name I might understand better…

RM: Giuliana Scimé.

EC: What does she do?

RM: She is a photography critic.

EC: But can she take photographs?

RM: I don’t think so…

EC: Then how can she talk about photography? Obviously she made this mistake and wrote such bullshit because she does not practice photography. What can she know? If she is interested in this sort of things she should sit at the police headquarters instead of being a critic. If this is her way to research she should start researching herself. When you search for the dark side of everything it means that you have lost the desire to talk about a photograph, the pleasure to look at a beautiful thing, and to deal with Giacomelli’s journey. It means that you are looking somewhere else. One studies all her life for what? If you review a photography exhibition on a newspaper you’d better focus on the images than put down coarse conjectures. In my opinion, that is unfair.

RM: Speaking of the relationship between art makers and art writers what do you think of art criticism?

EC: Critics don’t understand a thing about art, they just talk up what is fashionable. Real artists sense what is good and they formalize it. Whether you like it or not, an artist always brings a great contribution, with or without criticism. In fact, criticism muddles things up and promote second-rate artists. Just consider that art has been fashionable throughout the last century, do you think this is normal? Do you really think that art is for everyone? In short, only the artists can truly understand the contribution I mentioned earlier, the rest is just habits, curiosity or decoration. Clearly there are extremely famous jacks-of-all-trades specialized in their signature works. I find nothing bad about them but what do they have to do with art? It has always been this way. Think of Piero della Francesca. For three centuries he had been considered a “minor” painter until Longhi came along…

RM: There comes a critic…

EC: Don’t get wrong. Before being a critic, Longhi was a great writer who made you love Piero as novelist would. On the contrary, when he plays the critic, that is the fan, he makes such huge mistakes as when he defines De Chirico the “worst bad painter” or when he regards Carrà as a good painter. Carrà may have been fairly intellectual but he certainly was not a great painter, neither was Boccioni. Not to mention that the 1960s criticism failed to see the importance of Lucio Fontana during his lifetime. Not to talk about those manqué painters who have become curators, like Francesco Bonami.

RM: Then, what are we to make of Achille Bonito Oliva, a critic whose activity was instrumental to discover as well as to support the Transavanguardia?

EC: Bonito Oliva is the best because he is the most debauched. Beside that, every artistic journey is started by the artists; it is them who start that sort of automobile that Art is. Critics jump on it and make conversation along the way but they never drive.

RM: Art is an idea, a form of thinking the paternity of which could be discussed at length…

It seems that in your opinion artists are the creators of Art but also its only legitimate recipients, is that right?

EC: All in all, that is correct.

RM: Going back to that which relates Giacomelli and yourself, what do you do in a ditch? Do you stare at the stars?

EC: No. Stars are sentimental. In a ditch you look at the frogs. You may like or dislike them but you can’t avoid to look at them because their croaking catches your attention.

RM: As this catalogue clearly shows, you and Giacomelli seem to share a dismal worldview. The leitmotiv is death, the end. Your eerie shadows appears almost everywhere, it looms even in the gayest images.

EC: That is right. To sum everything up: in a ditch you look at the frogs because they make noise, because you like them or are disgusted by them. You look at the stars once you are dead.

I hope Mario stares at them now.

[English translation by Anna Lovecchio]

FOTO 1 > MARIO GIACOMELLI

FOTO 2 > MARIO GIACOMELLI

FOTO 3 > ENZO CUCCHI, photo RM